Stanko Pavleski talks about the book as an artistic expression

Published on: 14.01.2017

An interview with Stanko Pavleski, 25.01.2017, Private Print Talks, Private Print Studio

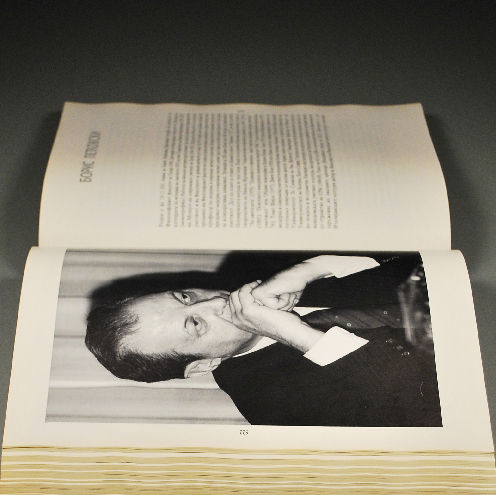

Stanko Pavleski (1959) is an artist and a professor at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Skopje. He is the first Macedonian artist who in the period 2002-2012 extensively researches the book as an artistic expression.

Stanko Pavleski during the interview, at Private Print Studio, 25.01.2017

PP: Our work as publishers of art books includes activities, such as archiving artistic materials, research and curating exhibitions. As part of these activities, meeting and conversing with artists is helpful to our work, and, we hope, by publishing them, these conversations could be of use to other researchers as well. Especially when you take into consideration that collecting materials about the practice of our artists is challenging, the best way to get to detailed and relevant information is still by contacting the artists directly. Our institutions are facing difficulties in systematic organization of the archives and the data of the artists. In any case, it is probably expected that we begin this practice with an interview with you, because of your work and use of the book as an artistic expression.

SP: I had a similar experience when using the archives of our art institutions for the artists that I couldn’t contact in person [for “Book beyond the Covers”]. In the Museum of Contemporary Art in Skopje, Lile Nedelkovska was devotedly working on that, but that sort of problems, unfortunately, are still present, even though the people there were making quite an effort, still there is a lack of organizational work. But, look, you remembered that there is a material of this nature and that someone once worked on something in that direction, using the book as part of a wider project, or as an artwork for itself, because of the possible images that the textuality draws us in. While we read we are engaged in a certain visualization that comes from what is a challenge for the author in his thought process. When we read we see in pictures. However, if you intend to work on the book as a specific artwork, that work should be seen through the book, as if it is the basic element upon which everything else is built on. You should have a vision that you touch a material to continue the project afterwards, and you build it upon a constant interest on sensed ideas to proceed with the project. It is clear that it represents a sort of matter, and a faith in that material.

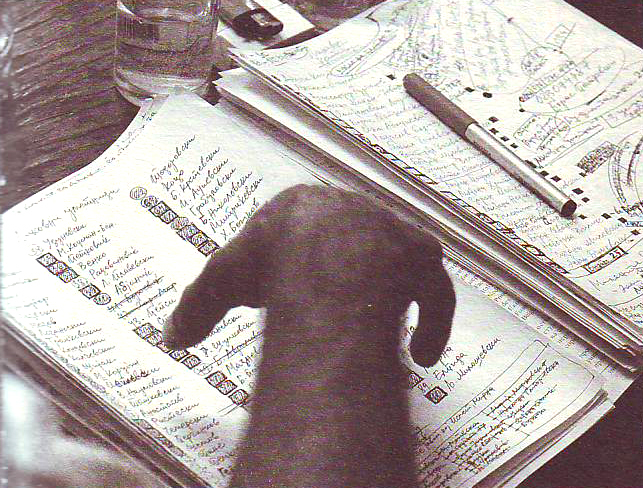

From the research for "Book beyond the Covers: My Anthology – Macedonian art and critic 1954-2004", in: “Tome Adzievski & Stanko Pavleski, Cinema Napredok 3, Trilogy – Province”, MSU, Skopje, 2006, p. 85

PP: The key element, while researching your work, seems to be the transformation from sculpture and its materiality to the book as an artistic expression. Two questions come to mind in this context. What is the thing that is left behind from the sculpture when it is transmitted into the book? And, whether the art book as a medium was researched in the context of our contemporary art history?

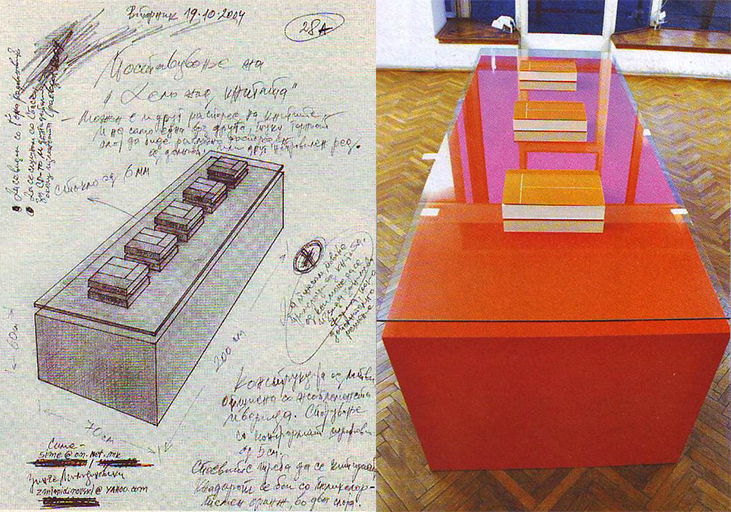

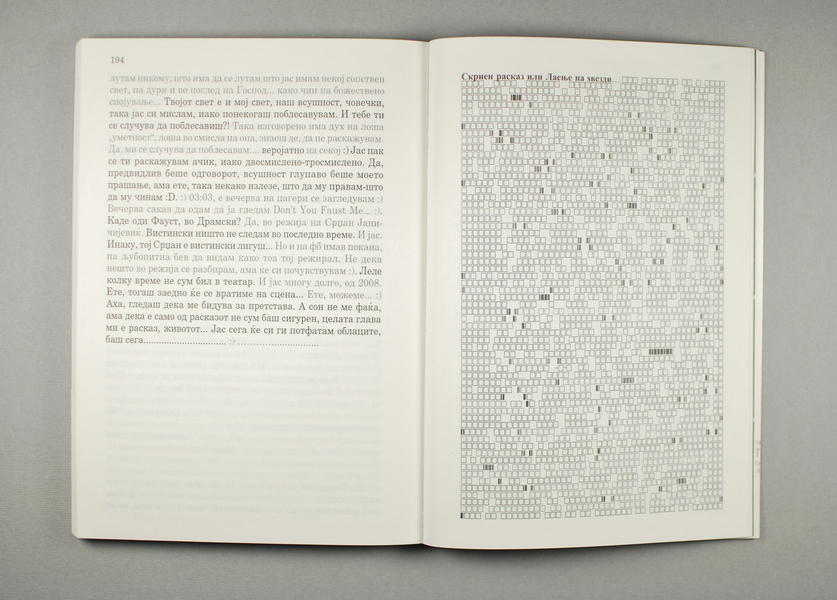

SP: You know how the results come in the process of creating, by sensing a field that catches your attention. I love the book, clearly. I try, as much as I can, to implement its textual nature, but also the book as a form that conceptually, with its material body, can find its way in the possible variations. While reading I imagine; the language carries visaulity. On one hand, we have the visuality that the book permits, through its incorporation in a certain concept, and on the other, its textuality that actually took me to the project “Written Art”, which is definitive, it is primarily literature. This project, for instance, includes 23 stories written in the period from the summer of 2010 to the summer of 2011, during which I took upon the task to write as much as I can about any art concepts that came to my mind. So, it is indeed a written text, literature; but from a different angle, if you think of it in its form, those are five hundred or thousand books that create a bigger block, it is a formal state that you could play with, in a way, also in the context of the form; you could build it as if it is a building material of a usual sculptural nature, especially when minimalism is close to my heart. But, even if we put that aside, if we concentrate on what is written, you could find there a great deal of material that doesn’t get to be visualized; but the word has the power to create an atmosphere, to transmit a state, so this matter, only by that, becomes visual. Something in this sense, accenting the book in a project, is the example of the “Work beyond the Book”, where the book “Book beyond the Covers” is incorporated in the sculptural body of the work. The work has a cuboid base, on which three books are placed and on the top of them there is a glass – two meters on one, this creating the idea of separation of two things, up and down through the transparent, because at the same position of the first three books, above the glass, there are placed another three. This evokes a certain play, through this positioning, the transparency and the mysterious play on the essential meanings of the basic elements of the work, all the way beyond the content, where the book comes first as a visual element as well, calling you to emerge in it and its secrets.

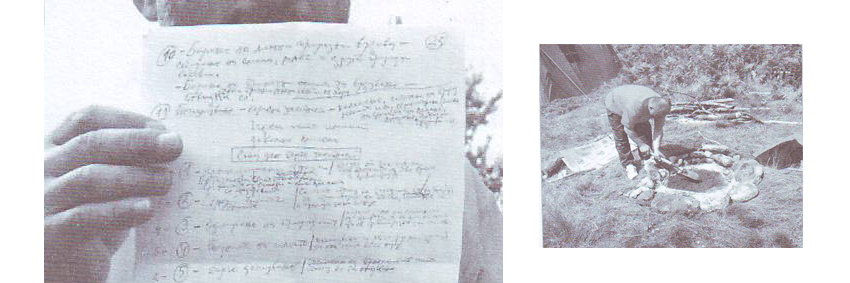

Stanko Pavleski, “Work beyond the Book”, left – a sketch; right - installation

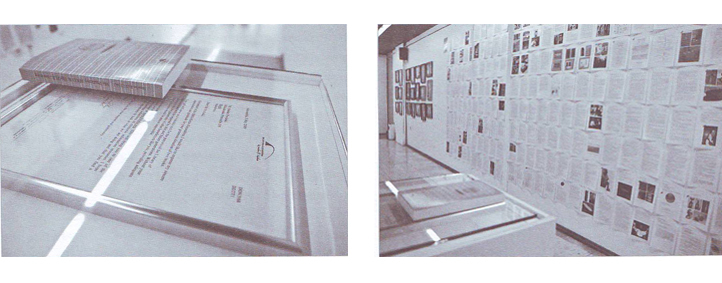

On another occasion, the book “Me Ptolemy MKD & H.E. Nothing” was exhibited with all its pages spread on a wall, including the covers. The whole material was printed on pages in A4 format, stretching their A5 format, so if anyone wanted, could read a piece of it. Some of the comments were that it is impossible to read all that text, since it’s a whole book, as if I was expecting that from them. However, the concept of the work is conceived as such, in the interspace, actually you have to sense it, see it; and in the same manner as a painting hanged on a wall is seen, that’s how this works too, it should be seen, because the artist offered it that way. The painting also invites you to come closer in order to “read” some detail, so it is in this case as well, if you are curious, you will not miss to read something of what is written. You start from there, then the spectator evaluates if there is a way to communicate with it. In the work the artist implements the communicative function as well, if that is what he wants. Or he follows his own vision, independently of the audience. It seems to me, however, there is no serious author who doesn’t have the audience in mind, out of respect towards his work, however arrogant this may sound. I have always been against the official values, provoking the energies for specific approaches, locations, topics, methods in art, and therefore the audience as well.

Stanko Pavleski, "Projection Balcony: Alexandria 2009" - exhibition

In the Macedonian art scene and the art scene in general, the conceptualists have similar approaches in leaving a bigger space for the textual in their works. Macedonian artists, it is true, have used a piece of text, in the past and especially more recently. This practice was treated from the critics as: ‘where does the art with paper go’ [Nebojsha Vilic]. The problem is in locating the work. Because you cannot stop halfway, either you bring the idea to the end or you don’t start at all. If the text is a substitute for something that is missing in the work, then you should do that by visual means. In the case the textual matter is the material you are going to work with, then you should resolve these questions, how to proceed more clearly and adequately, without any unnecessary noise.

PP: So, the transformation from sculpture to book doesn’t come as a result of liberating from the spatial dependency of the sculpture, but as a result of identifying that the text is equally visual and spatial act, implemented in the sculpture, and that the final product is, and should be treated as, a sculpture…

SP: Or an artwork in a wider sense. With time the concepts got widely transformed, so there was a need to redefine them. For instance, Rosalind Krauss in her book talks about the sculpture in a wider field. A new space is opened. Furthermore, with the postmodernism in the mid-80s, when for the media wasn’t necessary to be precisely defined, the sculpture is finding its place in the performance as well, because of the form, the body, because it uses some of the most important aspects of the sculptural. There was mixing of the media. The postmodernism simply dismissed the principle of specific definition of the art fields as a strict position.

PP: In our cultural context, the postmodern artwork seems to be unable to fully realize the syncretic idea, so it is usually perceived as being in two different locations - the creation of the artwork and its explanation. But, in your case, through the concept of the works, an amalgam could be recognized that unites both of these segments.

SP: Probably, if we attempt to simplify the picture of the nature of my work. But, I have always looked at things in a way that there are some things that are not easy to be explained, or to be explained with the right words. I believe that - and the practice teaches me so - the work should keep something mysterious in itself, to pose questions. In that sense, I try to let the work has that in itself. Definitely, it is a kind of unification of the artistic, the sculptural in this sense and the textual, generally speaking.

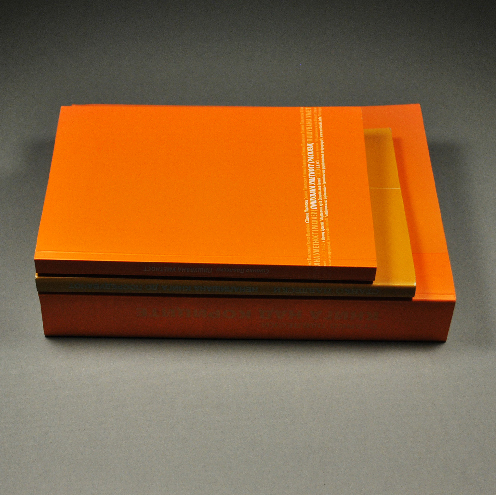

Stanko Pavleski’s books: “Unwritten Book to the Mediator” 2002, “Book beyond the Covers” 2004 and “Written Art” 2012

I work on finding a certain location, such as the book, where I could contain everything inside. Among my works, which tread in the direction of building the book in this sense, you can find a calendar of 70 pages, that again is a location, a frame, in which you could put different things; or there is a folder that asks for additional action from the audience, to open it, take out the material and take a look at it. There is art that you can access at first glance, and there is that kind that needs more time.

PP: In the process of your work, do you have the book on your mind the whole time and is it a part of the ephemerality of the process itself, or the book is the final element that comprises the ephemeral processes in a form of a document?

SP: Usually it happens that they are two parallel worlds. We couldn’t consider this relationship with the book as ephemeral. Probably, for example what happened to me/us during the work on the project “Artistically through the Phenomenal”, in an open space. The project was a call for the artists to join and dwell in nature, so everything you could imagine that could happen there, to create, to talk, sometimes about art, and from that experience, on the location or a posteriori, to create a work, even though, at first, we thought that the project was closed by documenting the expected events.

PP: Is the background for these activities, their documenting and interpreting, the idea of the fictitious publishing house?

SP: I am not a slave of the term publishing, and why would I be. I think of myself as a publisher. Is it going to be an accumulative object from this nature [a book], or in some other sense – a video material, folder, calendar - all that represents a sort of accumulation, location, such as the book does, except the ways and the method to come to that publishing accumulation are different and specific. There, in the book, there is visual material as well as text; some objectivity could also find its way there. What do we practically do with the folders? There is a great deal of wandering around through the folders, through photographs and documents, until you find the required data. The book, as well as the folder, is an accumulative object. If you’re curious and open it, worlds open in front of you. So, probably in the frames of the fictitious lies the problem, and in that context so does the idea behind the fictitious publishing house, because my feeling, though justified, neither intends to nor can problematize the term, but as an artist I stretch it through a project, the same way my experiences with treatment of the book are part of my intentions to test the extensibility of the artistic frames.

Promotional materials for the fictitious publishing house O.E.O

PP: You tend to create, in first place, a visual work - a book, where different types of information will be accumulated?

SP: Yes, and by the way to put into form what the artistic intent and condition keep closed, so it could be opened and discovered. I felt the same when I worked on “Written Art” and when I worked on the catalogue for “Artistically through the Phenomenal 2004-2014”. Five events that should be included there and it doesn’t matter if you present them in a form of a book or contain them in a CD or video. But, you have to do it somehow, for history sake. Not because of the artist – even though the artist is the one who has to take care of his own work in the first place, so if the society doesn’t pay attention, the artist himself has to pay the proper attention, to create an image of himself, so he will leave a decent enough material for the generations to come. Aside from this, I don’t care for any other concept of the history, I am only interested whether we have an impression that we have done something important, no matter how subjective it is in a given situation.

At the end, we come to the main topic of our conversation, and it is, probably, in the context of the accumulative object. That’s exactly how we defined it with Zoran Petrovski, while he was working on the essay “Dying is Fun” in 2012, as part of the project “Publishing House O.E.O. 2002/2012” in the Museum of Contemporary Art. He was facing that challenge, so the writing of the essay wasn’t easy, because that material indeed created difficulties in finding the right definition. That is how, in the essay, we come to the definition of the book as an accumulative object, and really, it happened subconsciously in the process of work, leaving behind all topics of inspiration accumulated in the books and the perspectives of their presentation concept.

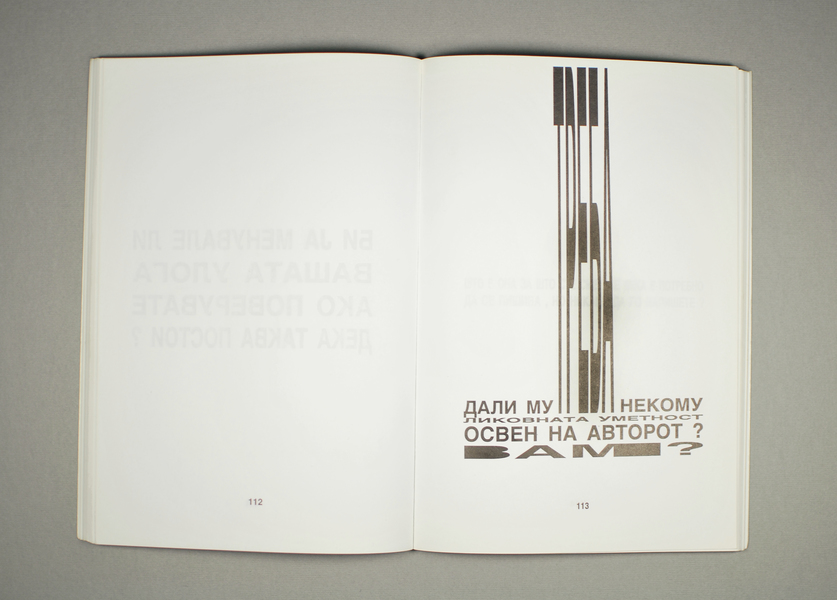

From: Stanko Pavleski, “Unwritten Book to the Mediator”, MSU, Skopje, 2002

PP: The first book “Unwritten Book to the Mediator” has a metalinguistic structure. Is it because the idea is to write down, accumulate ideas or matter, with the purpose to fill in something the culture lacks?

SP: Yes, and especially the “Unwritten Book to the Mediator”. Unwritten, not because it is empty - there are only some questions to the mediator, to the critics - with that word I intend to provoke them, that they are mediators with the audience. It is created to accent something that, at the time, I considered to be a negative direction that the art history and especially the art critic were taking - that is the entry of the NGOs. I have collaborated with all of them, I don’t have a problem with that, but I noticed a condition that influenced losing the initial of the Macedonian artist. You cannot say that the Macedonian artist is not informed, but when you impose the method in which the art should be made, and when in those open calls there were always demands to the artists, it offended me in a way. They always demanded something, why don’t they move a little, talk, ask, or that is done behind the scene. That is how the book begins: “The initial is a sacred place of the artist”. If an open call states that the artists should follow these particular rules, then you are taking from me the possibility to open my personal matter. On the other hand, I address the mediators, the critics, because they are in communication with the system, by the power of the word. Why have the literates during the Socialism been closer to the Government? The Government needed them. Through them it was possible to disseminate the ideology easier. That wasn’t that easy with the visual arts.

So, the book is a result of the revolt towards the program of the Contemporary Art Center (CAC), Kultur Kontakt, Pro Helvetia, because of the trap behind his Highness the Open Call and the agenda of its stakeholders. Inside there are two of my stories, and dreams as well. That’s how the narrative element begun and ended in 2012 - with “Written Art”. Primarily, it is about questions and comments on the state of the art criticism, fallen into apathy, or some kind of automatism with which the critics write, without any devotion or desire, call it a passion, without any soul. The book includes parallels with the literature I was interested at the time, to back the thesis. There are also texts of our literates, Bogomil Gjuzel, for example, there is one beautiful story by him, “The Typewriter”, that I always recommend to my students. I say, it’s only ten pages, but those are thousand worlds. We can pervert the familiar phrase ‘one picture – thousand words’ into ‘one page – thousand pictures’.

From: Stanko Pavleski, “Unwritten Book to the Mediator”, MSU, Skopje, 2002

PP: There are also typographical drawings in the book…

SP: Yes, as if it tends to pervert the textuality, to create a trap in the reading, so you cannot leave it at once, so you would think of the text matter for a while. You’re there only while reading the text. Usually, unconsciously, we go from one concept to another, and the question is do we spend enough time with what is written.

In this sense, when the sculptural is left, i.e. the standard state of the sculpture, where does the work occur, what exactly occurs? Beside the concept of word-image defined by Wittgenstein onwards, through the category of the power of the accumulation, the basic element incorporative in the additional sculptural work is where the whole of the work is contained. In some sort.

PP: This project begins in 2002 and ends in 2012. From this perspective, do you think it can be republished, redefined? Is that decade left to be a monumental sculpture?

SP: They took a proper form, and onwards if we follow the problem of the accumulative, which means that everything could be thrown on certain surface and that would present itself like a pile of waste or gold, no matter. My interest in this sense, here, can be closed. After 2012, the problem of the narrative appears in some other works, but not like a matter that can be developed in this sense. I combine photographs and narration. When there is a real reason for that.

Let me share one example. During the project “Patem 365”, at a location in the village Konjsko, in Prespa, I had an idea for a project that was to be closed by taking photographs of my writing on water. So I looked for some feathers from the cormorants, from the gulls, in that area, or on Golem Grad, the island, I even looked in the cane by the shore, tempted I took a cane or two and spun them in my hands, asking myself is it better to write with a cane on the water the thing that comes to my mind, or with a feather, no matter if it isn’t from a goose. That is one part of the whole matter. The guys around me took pictures, and we closed that story. But, I came to the location with a few ideas. Am I going to realize them all, is something going to be left behind, and you can’t realize it at a different location because it was planned in accordance with the specificity of this location? Those were the questions that I naturally posed to myself. All of those ideas that could have been realized at a location, but I couldn’t, were looking for a form of their own. But everything depends on the team and the conditions when you get there, which cannot always be easily predicted. Those photographs and experiences from the realized projects are closed in folders, and there it ends. In regards to the other, there was the dilemma whether they could be transmitted to a different place. I came to the conclusion that they could have the form of a story, as a place of realization, which made me happy, and so it was.

“Artistically through the Phenomenal”, in: Stanko Pavleski, “Publishing House O.E.O 2002/2012”, MSU, Skopje, 2012, p. 103

PP: What would you say all of these works, in their anthological nature, talk about?

SP: These works, primarily, talk about my relation to the time and the conditions, today, here, and beyond here. It is practically a description of time-space-condition in the frames of the visual arts, the institutions and the institutional. It’s not a declaration of war to them, even though some of the people recognized themselves and found themselves offended, and they are my friends, we are all friends, it isn’t a matter of war. The role of the written word in the visual arts is of great importance, from there the need to be better. I don’t intend to give lessons to the art historians, but I’ve noticed something that could be relevant, because there is the responsibility of the written word. Let’s try to picture things 30 years ahead - will people have the curiosity to try and find the material works of Stanko, a sculpture of three, five meters, something destroyed, something rusty. Everything will be about what you could read in the books. The research will mostly be done that way; the researchers are a bit lazy that way, also the information is hard to find, there are works that somebody took, didn’t bring back… I myself have been caught in the same trap while working on the material for “Book beyond the Covers: My Anthology – Macedonian art and critic 1954-2004”.

The importance of the written word is a mountain, from there comes the responsibility. History will be based there. It is the most communicative medium; furthermore, it is easier to take care of. I know what that means, don’t you believe me? It’s simple, I often say, I feel like my product will bury me under. What will I do to all the material, I need hangars or should I put everything on a stake, because of the freedom to create. How absurd and contradictory is this!? That is why we are incompatible with the world, because we still haven’t answered these absurd questions, and because of the inability to find the place of art and the artist, if it exists, and it existed. There isn’t a thing that will remain on this planet, everything, however, will be distorted, to their own destruction.

From: Stanko Pavleski, “Book beyond the Covers: My Anthology – Macedonian art and critic 1954-2004”, 2004

PP: The book, too, isn’t spared from this. These books could easily become rare. Maybe part of them will be destroyed and one will survive, so the search for it could be the same as a search for a sculpture in space. However, the new technologies change everything. Is the sculpturality with which you treat the book, at the beginning of this cycle, going to be redefined if it has to appear in a PDF document on a computer? Is this a total rejection of the sculptural in the project?

SP: It won’t contain its exhibition picture. For example, “Unwritten Book to the Mediator” was exhibited on a plexiglass shelf on a wall, with a purpose that the viewer could take it and it will have a space, an unusual exhibition quality by incorporating it in the artistic concept, even though the shelf is its natural position. A PDF document couldn’t replace that part, but if in its frames it contains this information, the image of the outer dimension of the book, could be visible. This often is the case when exhibiting the books, for example this publication can be found in a bookshop on a shelf. But then you ask yourself, how extensible is this concept and this playing with the meanings?

PP: A lot of information is incorporated in your books and in your other projects. How do you see the future in respect to this amount of information? What is the responsibility, the way it will come to the people, the discourses it will open?

SP: Looking through the materials that I haven’t seen for years, before this meeting, I remembered the project “Submarine TMRC”. That is a nice conversation with the colleagues Mile Nichevski and Vlado Lukash via electronic communication, on the occasion of a workshop for experimental drawing that Mile was organizing in Dojran. Knowing him from when he was a student, more carefree; and the idea was to document the workshop and to create a publication, or it would seem as it didn’t happen. And I say, let us create something, there is nice enough material, the people there are intellectuals, let them write something, let the author communicate on some other level. It is true that everything will find its place, but there is a chance that a lot of things don’t find their ways. It depends from the artist, from the family, after his death, from their care, as well of that of the society. We don’t know what might happen, even if the values were extraordinary. Visuality is a hermetic state, even though a lot of people trust the sight, and even though there are a lot of signs there, the reading of visual concepts is not easy, especially for the less informed.

I am not certain in any precise or non-metaphorical answer, especially on the last part of the question, because the generations can’t take a break from the problems of their own time, let alone to have a perspective of continuation and outcomes. I think, I might be wrong, that is also possible, I also forget that you too are from the generations that I talk of.

From: Stanko Pavleski, “Written Art”, 2012

PP: You say that a writer knows when he has written a good text. Are you as well conscious when you create a good work?

SP: Somehow I know, yes. The experience teaches me too, when in the atelier you create something good, you are able to feel that as well as recognize it, the question is only do you believe in yourself and your values enough. If that is clear with you and you don’t have doubts there, then you know that you have made a good artwork. You would feel it by the trembling of the intellectual level as well. It has happened to me once or twice, that kind of state, when it really feels like a conversation with the gods. When you see the result in front of you, when all of the chakras open, and when you really want to open everything in yourself and to converse with whatever energies there are… Is it going to be recognizable to the other? If the state isn’t fake, I believe, the other will feel it too.

But, nothing comes from itself, things don’t just come up. You need to be really devoted.

PP: Thank you for this detailed conversation.

SP: Thank you.

\\\\\\\\\\\\

Books:

2002: Unwritten Book to the Mediator, Museum of Contemporary Art, Skopje; part of the installation Eyes wide open, Museum of Contemporary Art, Skopje, 2002;

2004: Book beyond the Covers: My Anthology – Macedonian Art and Critique 1954-2004, independent publication by the artist, Skopje; in A Work beyond the Book, part of a wider project Cinema Napredok 3: Trilogy Province 2, together with Tome Adzievski, Cultural center, Debar, 2004 and Museum of Contemporary Art, Skopje, 2006. The work is a part of the permanent collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Skopje.

2005: Project Preface: How do I write a good review as art critics do?, as part of the project Kinetic Painting by Spase Perovski, Art Salon, Veles, 2005;

2009: Me Ptolemy MKD & H.E. Nothing, independent publication by the artist, limited edition of ten books in Macedonian and English, Skopje; part of the project Projection Balcony: Alexandria, Gallery of the Jesuit Cultural Center, Alexandria, 2009; officially donated to the Alexandria Library;

2010: To be Announced: Written Art (Exact Project), Three Introduction Stories, independent publication by the artist, Skopje; part of the project with the same name, during the event Artistically through the Phenomenal 4 (artistic action in nature), as an announcement of the book published a year later;

2011: Written Art (Short Stories), Publishing House Oknat Elva Ovoet, Skopje; part of the wider project Artistically through the Phenomenal 4 (artistic action in nature), 2011;

2012: Submarine TMRC Deadline, independent publication by the artist, Skopje; a result of the workshop of experimental drawing held in Dojran, 2009.

Events:

2012: Artistic action in public space, Written Art, Macedonia Street, Skopje: an improvised stand with the publication of the fictitious publishing house Oknat Elva Ovoet;

2012: Exhibition, Publishing House O.E.O 2002/2012, Museum of Contemporary Art, Skopje;

2013: Exhibition, Segments 2002-2012, Museum of Romanian Literature, Bucharest, Romania.