Ulysses: A Meeting Place between Joyce and Matisse

Author: Iva Dimovska

Published on: 05.04.2019

James Joyce’s works and writing techniques have often been compared to the works of visual artists, especially modernist painters. In a book devoted to the formation and development of Ulysses as a novel, Joyce’s friend, the English painter and writer Frank Budgen compares Joyce’s writing and even more, the resulting work to an impressionist painting: “All this complicated mass of material (that is the characters, their thoughts and actions, my note) is represented by Joyce as an impressionist painter might have rendered a view cross river - the foreground rushes, towpath and bushes, the water itself, the reflections of sky and opposite bank (church spire, roofs and trees), the boats and swans on the surface, the town and upward sweep of the thither bank and the sky over it all” (“James Joyce and the Making of Ulysses”, Frank Budgen, 92). A bit later he adds that Joyce’s narrative technique could be easily described as a “photographic representation of a stream of consciousness” that is similar to an impressionist painting: “[t]he shadows are full of colour; the whole is built up out of nuances instead of being constructed in broad masses; things are seen as immersed in a luminous fluid; colour supplies the modeling, and the total effect is arrived at through countless number of small touches” (93).

An exclusive, limited edition of Ulysses, illustrated by French painter Henri Matisse is probably the most famous example of Joyce’s collaboration with the visual. In 1935, American publisher George Macy offered Matisse $5,000 to create as many etchings as this budget would afford for a special illustrated edition of Ulysses for subscribers to the Limited-Edition Club in America. This edition was published in 1500 copies, each of them signed by Matisse and 250 were also signed by Joyce.

It seems that Joyce was excited that a famous artist such as Matisse would illustrate Ulysses and made some efforts on his own behalf to make sure that he had a fuller perspective of the novel. Richard Ellmann, Joyce’s biographer, writes that Joyce, knowing that Matisse had agreed to illustrate Ulysses for this special American edition, wanted to make sure that Matisse had some sense of Dublin and Irish culture before engaging on this task. So, he wrote to Thomas W. Pugh, an Irish acquaintance - and a knowledgeable Dubliner - asking him for help, in finding some illustrated weekly published in Dublin about 1904 (“James Joyce”, Richard Ellmann 675).

In this letter written during the summer 1934, Joyce says to Pugh: “Apart from the usual U.S. edition there is to be brought out before Christmas an édition de luxe with a preface by some writer and a series of 30 illustrations by the French painter Henri Matisse. He is at present in the south of France, doing them. He knows the French translation very well but has never been in Ireland. I suppose he will do only the human figures but even for that he would perhaps need some guidance” (Letters of James Joyce, Volume III, edited by Richard Ellmann, 313). After that he asks Pugh if he knows of any illustrated weekly as Ellmann mentions in his biography, so that he could show them to Matisse.

Joyce’s efforts to find suitable visual materials for Matisse probably most clearly reflect his own need for Matisse (and the world) to do justice to Ulysses, and not so much his heartfelt desire to help out the painter. But they also reveal the significant place Dublin occupies in Ulysses. One of Joyce’s most quoted statements goes: “I want to give a picture of Dublin so complete that if the city one day suddenly disappeared from the earth it could be reconstructed out of my book”. Rather ironically, Joyce mentioned this desire of his in a conversation with Frank Budgen, as they were walking down the Universitätsträsse in Zurich, where Joyce lived during the Second World War (see “James Joyce and the Making of Ulysses”, Frank Budgen, 69).

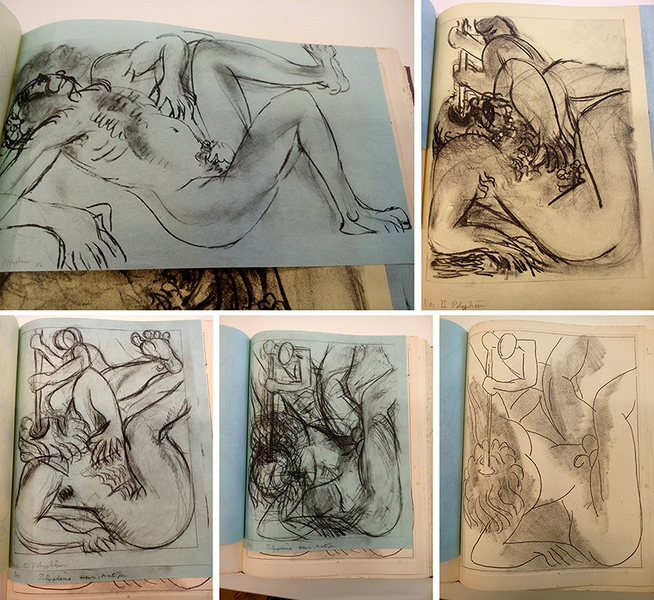

Matisse turned in six drawings that do not really have much of Dublin in them. The illustrations are based on six episodes from Homer’s Odyssey: “Calypso”, “Aeolus”, “Cyclops”, “Nausicaa”, “Circe”, and “Ithaca”. It’s been long accepted that Matisse did not pay much attention to Joyce’s novel, and based his drawings on Homer’s Odyssey, knowing only that Joyce’s Ulysses was also based on the ancient Greek hero Odysseus (Ulysses in Roman mythology). The popularity of this interpretation most likely comes from Ellmann who describes Matisse’s creative process, and, with that, the end of the Joyce-Matisse collaboration in such manner: “Matisse, after consulting briefly with Eugene Jolas (Joyce’s friend, my note), went his own way, in the late summer and early fall 1934; when asked why his drawings bore so little relation to the book, he said frankly, ‘Je ne l’ai pas lu’ (‘I haven’t read it’, my note). He had based them on the Odyssey” (675).

Aware of this, Joyce did not react particularly well to Matisse’s illustrations. In the meantime, his daughter Lucia Joyce who was a dancer and an artist started designing large initial letters (lettrines) that Joyce wanted to use for a book of his poetry, but unfortunately did not manage to do so without some effort. Almost a year after the letter he sent to Pugh asking him for some help with Irish materials, in the spring of 1935, Joyce wrote to Harriet Shaw Waver, one of his greatest literary supporters: “As for the illustrations for the U.S. edition they are yours for ever and ever. Amen. If they had been signed L.J. (Lucia Joyce, my note) instead of H.M. (Henri Matisse, my note) people would have had a different tale to tell. I am only too painfully aware that Lucia has no future but that does not prevent me from seeing the difference between what is beautiful and shapely and what is ugly and shapeless. As usual I am in a minority of one” (Letters of James Joyce, Vol. I, edited by Stuart Gilbert, 365). So, Joyce’s reaction to Matisse’s illustrations for Ulysses seems to have also been influenced by the difficulties Lucia Joyce encountered while trying to publish her designs.

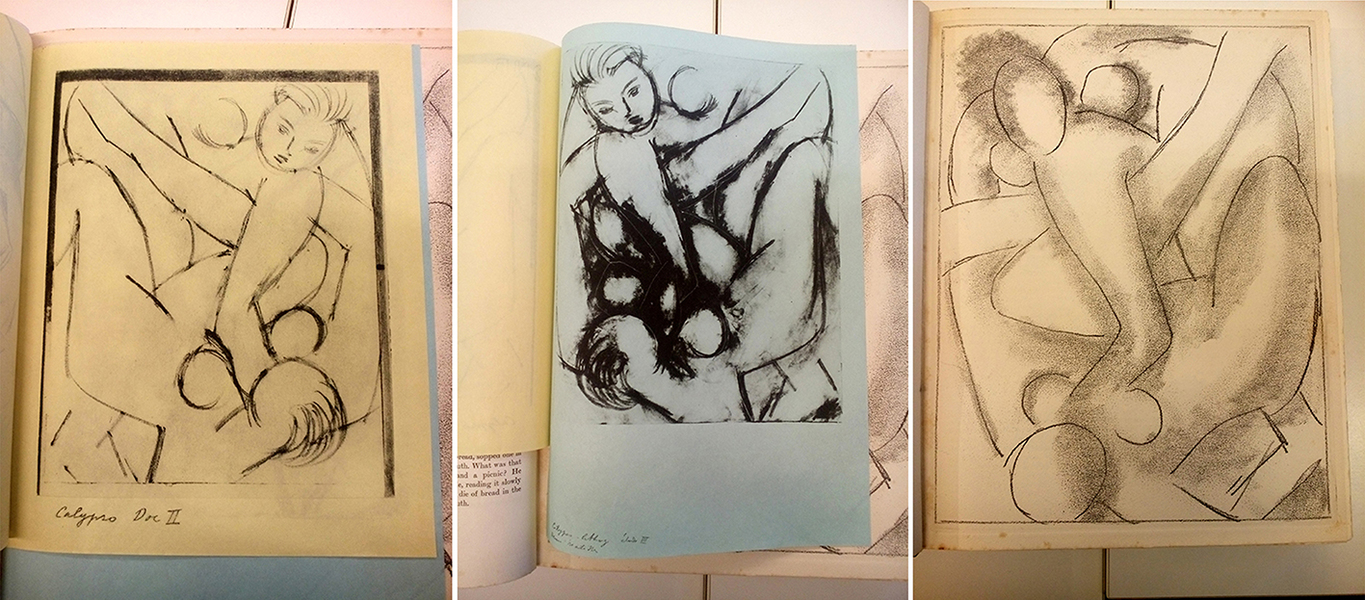

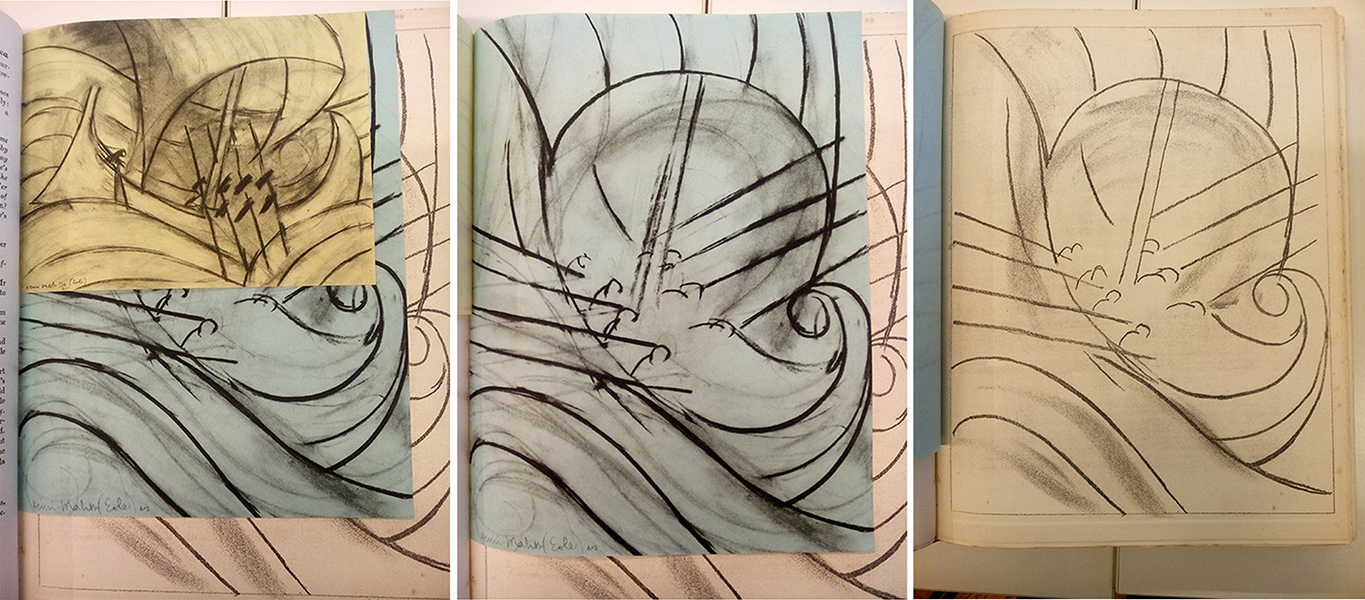

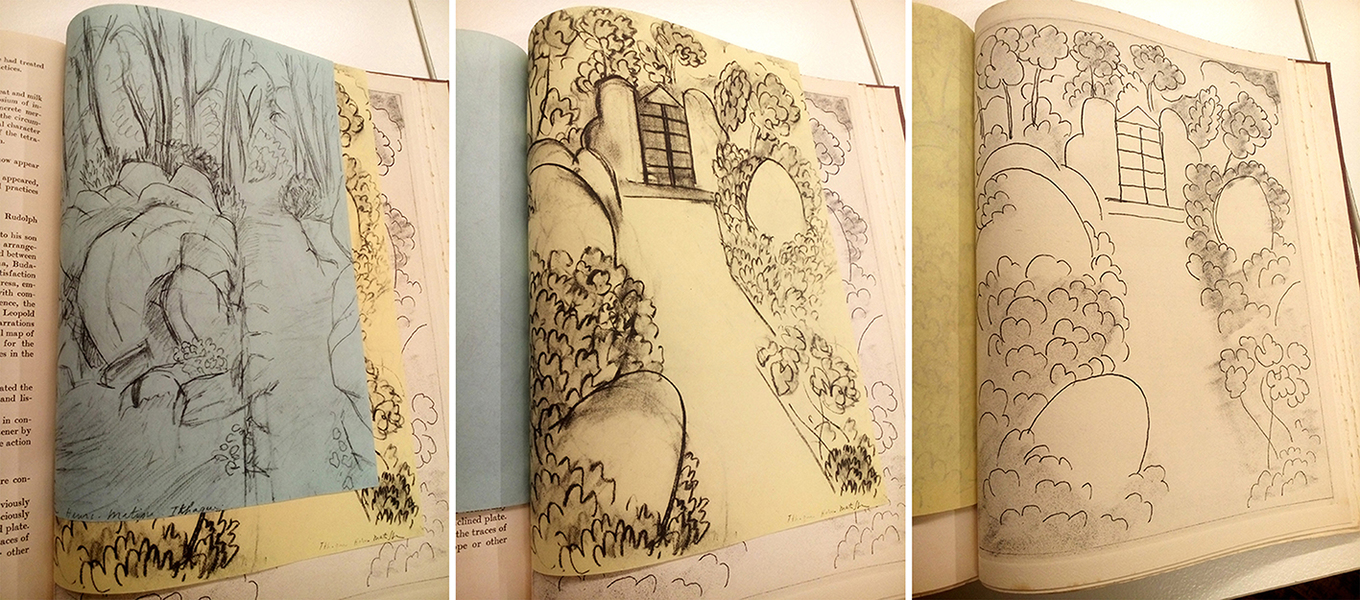

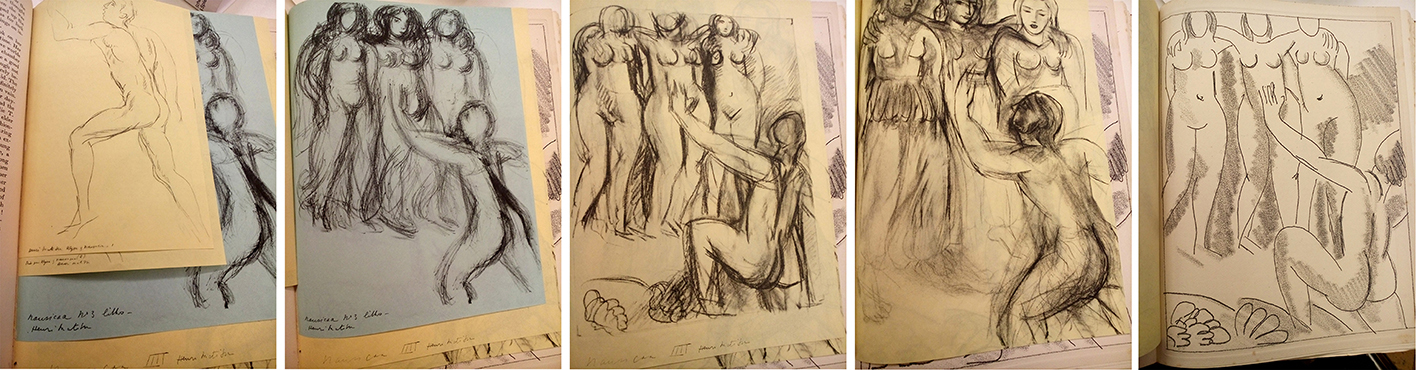

Nevertheless, the Matisse-illustrated Ulysses was published. The resulting limited edition was a large and attractive volume, bound in “full brown buckram” with one of Matisse's designs embossed in gold on the cover. Matisse’s soft-ground etchings that illustrate the six episodes are preceded by anywhere from two to five pencil studies, which Matisse sent along with the final etchings, following a decision made by Macy. The full-page etchings are located variously in the chapters they illustrate and are immediately preceded by the studies, reproduced on yellow or blue tissue paper of varying size (see “Joyce and Matisse Bound: Modernist Aesthetics in the Limited Editions Club ‘Ulysses’”, Knapp 1061). The preface written by Stuart Gilbert, one of Joyce’s friends in Paris, and author of “James Joyce’s Ulysses: A Study” (1930), one of the most significant early studies on Ulysses.

In an essay that explores the mutual modernist aesthetics of Matisse and Joyce, James A. Knapp has a different take on this “collaboration”. He claims that a few letters Paul Leon (another friend of Joyce’s) sent to Macy, the publisher of the edition, indicate that Joyce was actively involved in the planning of the edition, and had an interest in the artistic value of Matisse’s illustrations. Reportedly, Joyce disused the edition in a telephone conversation with Matisse in August of 1934, and in 1936, even after the letter he sent to Weaver, Leon assured Macy that Joyce’s interest in owning copies of the edition was proof that he liked it (see Knapp 1056-57).

Even if Matisse did not read the novel, he must have been familiar with its experimental style and technique; and his decision to base the drawings on the Odyssey was a deliberate one, claims Knapp. “Whatever the cause, Joyce's confidence in Matisse’s decision to base his etchings on Homer’s Odyssey ought to be seen as a form of collaboration, an affirmation from Joyce that Ulysses engaged with an aesthetic tradition that could be approached from more than one angle” (Knapp 1057). Shari Benstok offers a similar interpretation, stating that Joyce and Matisse seem to have a similar approach to the object of representation: while the presence of the Odyssey in Joyce’s Ulysses (that takes place on one day in 1904 Dublin) is subtle, or even parodied, Matisse’s illustrations bear no resemblance to traditional Greek forms, or are similar to the traditional representations of the episodes they are supposed to depict. She writes: “Joyce and Matisse are surprisingly of one mind in their artistic intent […] A common attitude in artistic approach - thoroughly modernist in its vision - links these two artists: the method of their art supports the supremacy of technique to all else; in its stylistic components, and in particular its experimentation with technical forms, this method assumes priority over its subject matter” (Shari Benstock, “The Double Image of Modernism: Matisse’s Etchings for Ulysses”, 455). Thus, both Matisse and Joyce have a similar relationship to Homer in their works, and with his decision to base the drawings on Homer and yet not present them in traditional Greek forms, Matisse seems to have been honoring Joyce’s approach to the Odyssey as well.

Joyce and Matisse, although independently so, had a comparable attitude towards the tradition they are drawing from and transforming. They both belong to a larger group of artists and writers who were creating their works in the period that is today known as “modernism”. Modernism, the major movement in Western literature and art of the first half of the twentieth century is often considered a period in which most domains of public life were underwent a revolutionary change. What we now consider modernism (lasting from around 1890s to the 1930s) was marked by “general diffusion of social alienation, the rise of the psychoanalytic movement, the disorientation brought about by the shock of the Great War and the increasing experimentation of almost all the contemporary artistic movements” (Denis Brown, “The Modernist Self in Twentieth-Century English Literature”, 1). While Joyce’s Ulysses ironically reinterprets the Odyssey, through fragmented narratives and the dissolution of subjectivity, Matisse’s drawings with their simple and experimental forms step away from realistic painting. Realized in two different artistic fields, their works are marked by some of the most significant modernist features: sudden breaks with traditional ways of representing the world and human interaction, experimental narratives, disrupted language, sexual ambiguity, fragmented subjectivity.

The 1935 illustrated edition of Ulysses is an exceptional example that represents these features in both narrative and visual register, and of a fascinating (even if failed) a collaboration between a writer and a painter that occupy such a significant position in their respective canons. They both seem to have been driven by a desire to control the work they were producing and had a similar modernist approach to the content they were representing. Even though aimed at a pretty exclusive audience, this Ulysses edition did draw more attention to both Joyce and the novel, especially in the American context. Its editor, George Macy – who conceived and designed the book himself – certainly played a rather significant role in this process, maneuvering between the difficult communication between Joyce and Matisse, and finding the suitable audience for this limited edition of a controversial book. Whatever the story of Joyce’s reaction to the Matisse-illustrated edition, or their personal interactions, this edition is, to say the very least, a rather rare example of a beautiful piece of modernist art, both visually and narratively.

\\\

Iva Dimovska is PhD candidate at the Central European University

Photographs by Iva Dimovska; Courtesy of Zurich James Joyce Foundation

Illustrations inside the book: © Succession H. Matisse

\\\

From the same author:

Ulysses: Publishing Notes - LINK