Ulysses: Publishing Notes

Author: Iva Dimovska

Published on: 13.12.2018

* James Joyce

James Joyce's Ulysses, often described as one of the most influential novels of the twentieth century and one of the most important works of modernist literature, focuses on one day - 16 June 1904 - in the life of Leopold Bloom, a middle-aged Jewish man living in Dublin. The novel establishes series of parallels between its characters and events and the ones of Homer’s Odyssey (Bloom is thus Odysseys, Stephen Dedalus, a young man who Bloom knows, is cast in the role of Telemachus, and Molly Bloom, Leopold’s wife, is Penelope) and it is composed of eighteen episodes, each of which carries the name of an episode in the Odyssey: the first episode is known as Telemachus, the second is Nestor, the third Proteus, the fourth Calypso, and so on: Lotus Eaters, Hades, Aeolus, Lestrygonians, Scylla and Charybdis, Wandering Rocks, Sirens, Cyclops, Nausicaa, Oxen of the Sun, Circe, Eumaeus, Ithaca, and Penelope.

The publication history of Ulysses is itself a sort of an odyssey, filled with hardships and multiple setbacks on various fronts, and one bitter-sweet final victory. In the first couple of decades of its existence, this modernist novel was a synonym for obscenity, indecency and lewdness, which made its publication extremely difficult.

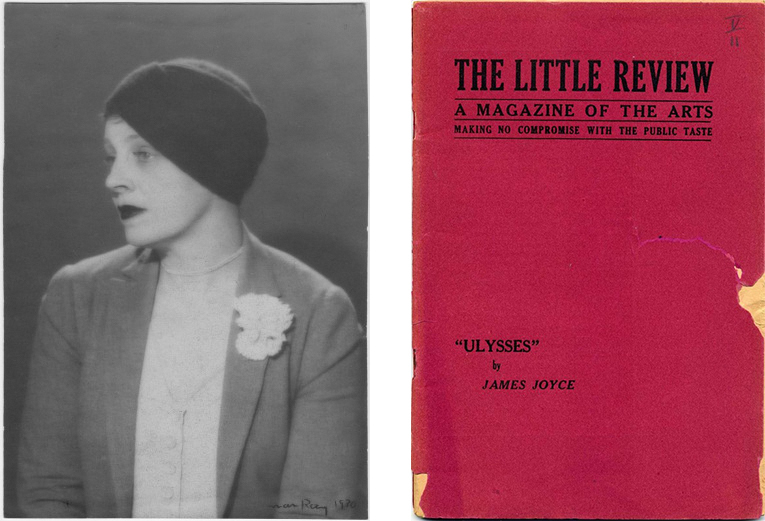

Joyce started writing Ulysses in 1914, and by 1918 he was sending typescript chapters to Ezra Pound to be published in installments in the American magazine The Little Review, published in Chicago. Having already dealt with many apprehensive and wary publishers and printers when trying to publish his short stories Dubliners in Ireland, Joyce knew how difficult it would be to publish Ulysses, an even more controversial book. Literary and cultural censorship was especially common both in the United Kingdom and the United States in the first half of the twentieth century, and publishers and printers “feared being prosecuted for defamation by means of the printed word, considered a public libel tending to produce evil consequences to society when blasphemous, obscene, or seditious” (Carmelo Medina Casado, “Legal Prudery: The Case of Ulysses”, 90). In simpler words, any kind of representation of anything deemed “inappropriate” or “obscene”, including defecation, masturbation, sexual activities, intoxication, even childbirth and menstruation (each of these detailed in Ulysses) could lead to an obscenity charge and a subsequent trial.

Aware of the dire situation, Joyce kept sending chapters (or episodes, as he called them) for publication in the magazine, hoping to both avoid charges and to lure the public’s attention through this very specific form of novel publishing, somewhat popular at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century. Admittedly, in the meantime, he was also working on the novel that was not yet finished and was constantly revising, correcting and emending parts that were already done and printed in the magazines, a process he would continue doing through the rest of his writing life, bringing much despair to his typists, printers and publishers.

** Left: Margaret Anderson, founder of The Little Review; right: The cover of The Little Review in which the first episode of Ulysses was published

In September 1920, a warrant was issued against The Little Reviewʼs publishers, Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap. This first legal battle over Ulysses followed a complaint to the District Attorney of New York County from a prominent New York lawyer, whose daughter had received the issue of The Little Review containing the “Nausicaa” episode, where Leopold Bloom masturbates on a beach, while watching a young girl. The preliminary hearing was on 21 October 1920, and the trial began four months later, on 14 February 1921. Only a week after the start of the trial, on 21 February, the court delivered the verdict, convicting the two editors of publishing obscenity. Each editor was sentenced to pay a fine of fifty dollars and the publication of further installments of Ulysses in The Little Review was prohibited (Carmelo Medina Casado, “Legal Prudery: The Case of Ulysses”, 91-92; Joseph M. Hassett, “Literature Meets Law in Court: The Trials of Ulysses”, 213-228 in Johnathan Goldman, ed. “Joyce and the Law”).

In the UK, there was not a trial against Ulysses, but the results were similar: no one wanted to publish Joyce’s works, risking a legal prosecution. However, in London, Harriet Shaw Weaver, the editor of the literary magazine The Egoist and Joyce’s devoted literary supporter throughout his lifetime, published five installments, from January to December 1919, containing three full episodes of Ulysses: “Nestor,” “Proteus,” “Hades,” as well as the beginning of “Wandering Rocks.” Weaver also tried, with Joyce’s approval, to publish Ulysses in a book form. In the spring of 1918, she visited Virginia and Leonard Woolf, who had their own publishing house, the Hogarth Press and offered them the manuscript for publication. Virginia Woolf had a rather ambiguous take on Joyce’s oeuvre, and especially on Ulysses, although she followed it through its initial publication in The Little Review in 1918, keeping notes on his techniques and comparing his work to the writings of other modernist writers. She believed that publishing a book of such length might be risky step a for a small press such as the Hogarth, since Virginia and Leonard Woolf were the only two employees that time and they printed the book themselves on a handpress. Understandably, Virginia Woolf was also afraid that Leonard would have difficulties finding a printer prepared to be liable in case of an obscenity charge. At the end, no agreement was reached and the Woolfs declined Harriet Shaw Weaver’s offer (Hermine Lee, “Virginia Woolf”, 439-440).

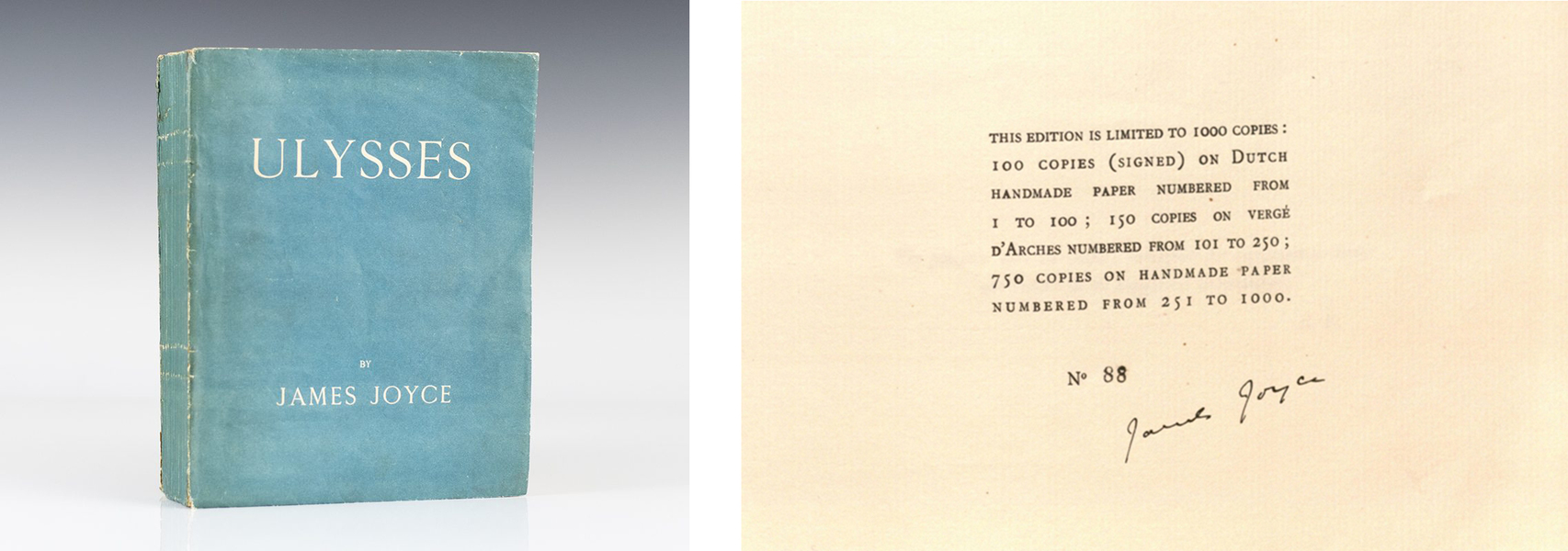

In such a way, by the end of the American trial, virtually the entire English-speaking world was united in opposition to Ulysses. In the following years, customs officials in these countries actively confiscated and destroyed Joyce’s novel, a state of affairs which dramatically prompted Joyce to claim that he deserved a Nobel peace prize (Paul Vanderham, “James Joyce and Censorship”, 4). Luckily for him, there was one brave, young, queer publisher who would decide to take a chance on Ulysses. In 1920, Joyce and his family moved from Trieste to Paris, where he met Sylvia Beach, the founder of the Paris’ iconic bookstore Shakespeare and Company, that at the time was a social center for the American and British expatriate author community. In her 1959 memoir “Shakespeare and Company” Beach described Joyce’s “complete discouragement” after The Little Review ceased publication: “All hope of publication in the English-speaking countries, at least for a long time to come, was gone. And here in my little bookshop sat James Joyce, sighing deeply. It occurred to me that something might be done, and I asked: ‘Would you let Shakespeare and Company have the honour of bringing out your Ulysses?’ He accepted my offer immediately and joyfully. I thought it rash of him to entrust his great Ulysses to such a funny little publisher. But he seemed delighted, and so was I […] Undeterred by lack of capital, experience, and all the other requisites of a publisher, I went right ahead with Ulysses” (57). Sylvia Beach then found a French printer, Maurice Darantiere, who was willing to print the book essentially on commission. They planned a first edition of 1000 copies (including 100 signed by the author).

*** Ulysses, first edition, Shakespeare and Company, 1922. Left: The cover of the edition; right: The inscription page with Joyce’s signature

Even though Joyce finally found a publisher and a printer willing to take on the novel, the end was not in sight: the process of printing the book itself was also complicated. Just finding typists who could create useable typescripts from Joyce’s manuscripts was a challenge. As said before, Joyce’s writing process was based on relentless (often last-minute) revisions, insertions and corrections, that transcribing them was sometimes nearly impossible. In addition, his unusual language and for many potentially offensive and hard to grasp content provided more difficulties for the typists. In her memoir, Sylvia Beach recounts another anecdote on how the printing was at one point held up because no typist could be found to complete the “Circe” chapter: “Joyce had been trying in vain for some time to get this episode typed. Nine typists had failed in the attempt. The eighth, Joyce told me, threatened in her despair to throw herself out of the window. As for the ninth, she rang the bell at his door and, when it was opened, threw the pages she had done on the floor, then rushed away down the street and disappeared forever. ‘If she had given me her name and address, at least I could have paid her for her work,’ Joyce said” (Sylvia Beach, “Shakespeare and Company”, 73). There was even difficulty with finding the right paper for the book’s cover. Joyce wanted the cover to be the blue and white, reminiscent of the Greek flag, but Beach and Darantiere could not find paper in a shade of blue that met with his approval. Finally, the printer found the right blue in Germany and had it lithographed onto white cardboard for the bindings (see Megan Mulder, “Rare Book of the Month: Ulysses by James Joyce (1922), ZSR Library).

Beach was hoping to have the first edition of Ulysses published by the fall of 1921, but the many complications in the printing process delayed the project for more than a year. Ulysses, in a book form, was finally published on 2 February 1922, coinciding with Joyce’s fortieth birthday, a fact he was very happy about.

At the same time, Harriett Shaw Weaver was determined to publish the first British edition of Ulysses, so after founding the Egoist Press in 1920, she managed to print two thousand numbered copies in 1922. Published by John Rodker, a Paris associate of Harriet Shaw Weaver, this edition was also printed by Darantiere using the same printing plates as Beach’s edition, in Dijon, France, and was presented in Paris on 12 October 1922. The British edition encountered censorship problems almost immediately, and most copies intended for the British market were confiscated by the authorities. On the bright side, these censorship strategies and the British and American ban put a lot of attention on Joyce’s novel that was becoming more popular by the day. Copies of the book were selling quickly at the Shakespeare and Company bookstore in Paris, with Beach’s edition being completely sold out by the summer of 1922. A copy of Ulysses was a popular souvenir for American and English visitors to Paris in the 1920s. Getting books into the hands of the many British and American subscribers proved to be more of a challenge, since the book was banned from distribution through the mail in both countries. But the always resourceful Sylvia Beach found ways to get around the official censorship. At one point she enlisted the help of Ernest Hemingway, who recruited a friend from Toronto (the book was not banned in Canada at that moment). A shipment of books for American subscribers was sent to Hemingway’s friend, who then boarded the ferry from Toronto every day with “a copy of Ulysses stuffed down inside his pants” (Beach, 96).

**** Sylvia Beach at the Shakespeare and Company; right: Sylvia Beach with James Joyce

And yet, the (mis)adventures surrounding the publication of Ulysses were far from finished. Following the novel’s unexpected success and popularity, an American publisher, Samuel Roth began publishing a pirated edition of Ulysses in his journal, Two Worlds Monthly. He printed twelve installments from July 1926 until October 1927. Joyce’s American lawyers took legal action claiming James Joyce’s name had been exploited without his consent; but as Ulysses was a legally banned book, the lawyers could not base their claim on copyright law. The legal proceedings took place on 27 December 1928, at the Supreme Court of the State of New York enjoining further publication of Ulysses (Carmelo Medina Casado, “Legal Prudery: The Case of Ulysses”, 93).

Unable to stop Roth’s unauthorized edition legally, Beach took matters into her own hand and turned to the international literary community for help. She composed a petition of protest with the help of a lawyer friend and began soliciting signatures from prominent figures, hoping it would sway the courts to stand up for artistic integrity. She invited some of the era’s most influential writers, critics, and translators to come to Shakespeare and Company to sign the letter and circulated it across borders throughout Europe. One hundred and sixty-seven prominent writers and scientists signed this text, among them Albert Einstein, D.H. Lawrence, Virginia Woolf, William Butler Yeats, Ernest Hemingway, Bertrand Russell, T.S. Eliot, H.G. Wells, Sherwood Anderson, W. Somerset Maugham, E.M. Forster, H.D., and André Gide. “I feel greatly honoured by Einstein’s signature, given so quickly and simply,” Joyce wrote to a friend. It was published in Paris on February 2 - Joyce’s forty-fifth birthday, exactly five years after Beach published Ulysses - and was reprinted in The New York Times on February 27 (see Maria Popova, “Sylvia Beach and the World’s First International Writers’ Protest”, Brainpickings).

In August 1932, a new and definitive trial to remove the ban on Ulysses took place in the United States. The publishing firm Random House provoked this trial by importing a copy of Ulysses to be seized by the customs authorities. The book, which arrived in New York in May 1932, included reviews of Ulysses pasted into it with the purpose of using them as evidence in defense of its literary importance. As foreseen, Random House objected to the seizure, and the case against Ulysses was reopened, with the final decision made known at the end of 1933, almost two years later. This time the court ruled in Ulysses’ favor, in a rather historic move against censorship and in favor of freedom of speech, significant both for the United Stated, as well as for Western democracies in general. The court’s decision, often quoted in Ulysses editions, states that “reading Ulysses in its entirety […] did not tend to excite sexual impulses or lustful thoughts but its net effect […] was only that of a somewhat tragic and very powerful commentary on the inner lives of men and women” (quoted in Carmelo Medina Casado, “Legal Prudery: The Case of Ulysses”, 96). The case against Ulysses in American courts ended with this decision, and so Ulysses was definitely admitted into the United States. This decision was eventually followed by other English-speaking countries - Ireland in 1934, England in 1936, Australia in 1937 (the ban was renewed in 1941), and Canada in 1949.

James Joyce spent eight years writing Ulysses, and most of his remaining life fighting to publish it. Like all (great) books, Ulysses most definitely exceeded Joyce’s intentions and expectations, becoming perhaps an unlikely symbol in a larger struggle against censorship, closed mindedness and the ways of the old epochs. The curios case of Ulysses and its publication history marks a definitive change not only in the reception and publication of (modernist) literature, but in the ever-evolving position of publishers and their public role. Its distressing and yet fascinating odyssey from an essentially unpublishable book to one of the most canonical novels in the history of Western literature illuminates the complex processes and networks texts are produced in and are a part of.

It would not be difficult to claim that James Joyce reformulated the use of language, reinvented the plot as a literary device and redesigned the novel as a genre. And yet, without his truly devoted supporters such as Harriet Shaw Weaver, who recognized the immense literary value of Ulysses; without a venturous and resourceful publisher such as Sylvia Beach who spotted the social, cultural, and intellectual significance of Ulysses; or even without the mercilessness of businessmen such as Samuel Roth whose actions globally popularized the novel, Ulysses would have never existed in, and managed to transform the literary world. Ulysses clearly shows that texts are interdependent not only on each other, but also on the communities that produce, correct, print, edit, publish, republish them, in an effort to preserve, modify, sometimes transform them, and that in such a way, inevitably keep them alive.

\\\

Iva Dimovska is PhD candidate at the Central European University.

Links to the photographs:

* James Joyce

** Margaret Anderson and the cover of The Little Review

*** Cover of the first edition of Ulysses and the inscription page of the edition

**** Sylvia Beach and James Joyce in front of the Shakespeare and Company