CURATING KNOWLEDGE: VESALIUS' PROJECT

Author: Ilija Prokopiev

Published on: 28.01.2019

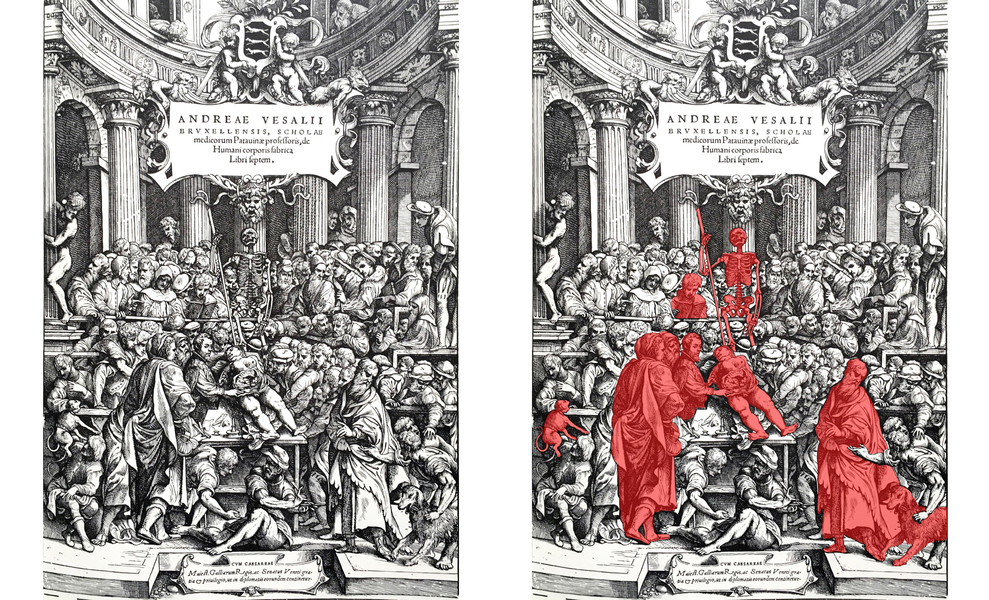

At the title page of the anatomical atlas De humani corporis fabrica (On the fabric of the human body) by the Flemish renaissance anatomist Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564) we see an illustration of an anatomy lesson. Vesalius is shown surrounded by a large number of people, housed in an imaginary architectural ambient in the style of Palladio, standing next to a table on which cadaver with open insides is lying. In the front segment of the illustration, right next to Vesalius, we can see the ancient fathers of medicine Hippocrates, Aristotle and Galen. Two animals (a monkey and a dog) are also illustrated symbolizing the old way of studying anatomy by dissecting animals, while centrally a skeleton is displayed, which, according to Vesalius' teaching, assumes a central place in the study of this medical discipline. But what keeps the viewer’s attention is the atmosphere created by this illustration. In those days, theaters for anatomical dissection, often made of wooden constructions (with not very large capacity) and located outside the university buildings, were probably very easily overcrowded. Squeezed Renaissance medical students with their heads and torsos hanging through the wooden benches trying to look at the open abdomen of the cadaver lying at the dissection table was probably the usual atmosphere of Vesalius's lectures at the University of Padua, Italy. Not all students could hear the professor's speech and many of them failed to secure a place from which they could see anything, so they would often leave the lecture hall. Interest was undoubtedly enormous. This was a time during which the practice of dissection of human bodies for the purposes of medicine was a very new and controlled right. Vesalius' academic and privileged position allowed him this right, enabling him to challenge the authorities of antiquity and promote progressive and reforming processes in medicine. Thus, Vesalius becomes Galen's greatest critic, identifying a number of errors in his anatomical descriptions that were based on the sectioning and observation of animals.

Title page of De humani corporis fabrica (the red marks are made by the author)

Hence, recognizing the possibilities of the era, Vesalius reinvented the study of human anatomy. His acquired experience pointed to the danger of using old medical practices without their reassessment. According to him, this led to a circular repetition of errors, which could only be changed if human anatomy is methodologically studied through direct observation. This new method of work has changed the whole course of understanding and knowledge of the human body and has led to the reorganization of medical education. To this end, Vesalius created the first modern anatomical atlas, where he summed up the outcome of the new scientific approach and made it available not only to researchers of the human body, but also to all those outside the university halls. With the publication of the atlas De humani corporis fabrica Vesalius overcame any previous attempt to create a similar work in medicine and art, deserving the position as a reformer in the history of medicine and medical illustration. With Vesalius, for the first time in the modern history of medicine, the directions of the veins, the anatomy of the heart, the outer and middle ear, the mediastinum, the mesentery, the fornix in the brain, the thigh bone (femur), the long bone in the upper arm (humerus), the breastbone (sternum), the triangular bone at the base of the spine (sacrum) and the upper fixed bones of the jaw (maxillary), the arytenoid cartilage in the larynx, the meniscus, and the yellow body of the ovaries (corpus luteum) were correctly anatomically represented.

De humani corporis fabrica is a modern structured medical atlas, inventive in the template design of the page, the structure of the text and the illustrations. The Atlas was printed in 1543 in Basel by the publisher and printer Johannes Oporinus. During that period, Basel surpassed all printing centers across Europe, especially taking the primacy before Venice, with a number of top printers who perfected the printing of books. It was the home of publishing houses and printers like Johann Froben, Adam Petri, Andreas Cratander, and artists like Holbain and Urs Graf are also mentioned as an important part of the story of printing and graphic in this city. Despite running a small printing house, Oporinus enjoyed its influence due to the advocacy of progressive and inventive approaches not only in the selection of books, but also in designing. For example, the first Latin version of the Quran was printed in the printing press of Oporinus, edited by the Swiss Orientalist and Protestant Reformer, Theodore Bibliander, an act for which Oporinus paid with a prison sentence. Also, Oporinus left the widely accepted font (Heavy Roman Type) and replaced it with much more delicate fonts that allowed for a more compact distribution of text on the page. But despite all this, Oporinus had some additional personal advantages that were crucial for Vesalius to favor him among all others. Before starting his publishing and printing work, Oporinus began his education and career as a medical student under the mentorship of Paracelsus, and later continued working in academic circles as a professor of Latin and later Greek. These additional qualities ensured Vesalius that Oporinus would produce a flawless edition of De humani corporis fabrica, bearing in mind that Oporinus had knowledge of medicine, but also knowledge of Latin and Greek, the two key languages used in the atlas. So, the only concern Vesalius had was the successful printing of the illustrations, to which he devoted the greatest attention.

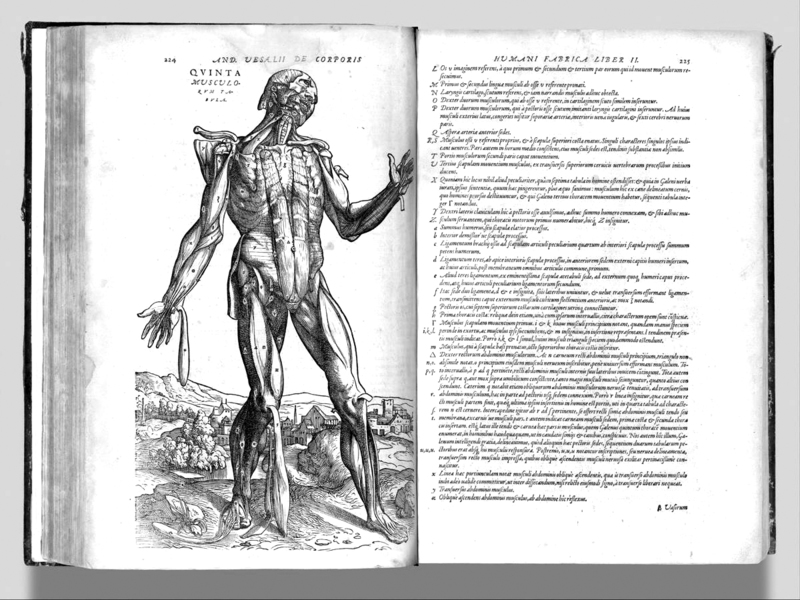

Inside pages of De humani corporis fabrica

Together with the printing plates, Vesalius sent Oporinus a cover letter explaining his design and intentions, and at the same time, in a subtle way, through including bad printing examples of books, he made sure Oporinus knew that the print must be flawless. The letter points Vesalius's neatness in organizing the entire project. He sent the plates with detailed explanations and instructions on the structure of the book and the organization of information in order to avoid confusion, and thus to prevent potential mistakes.

The Atlas is divided into 7 chapters (books): Bones and cartilage, Ligament and muscle, Veins and arteries, Nerves, Digestive and reproductive organs, Heart and associated organs and Brain. These 7 chapters include 20 full-page illustrations and over 200 within the text. The text pages are organized in three fields. The main body of the text is the default, centrally located on the page, while additional annotations are placed on the pages of the main text. In the internal margin of the page, as Vesalius explains in a letter to Oporinus, there are references pointing to the illustrations, and on the external margin of the page there are comments that serve as conclusions. As reference to the illustrations, annotations are encountered, as well as Latin or Greek letters that correspond to the letters that are an integral part of the illustration itself. Calling this Index method, Vesalius creates a system that facilitates learning. The reader can simply follow the picture and the text simultaneously.

Inside pages of De humani corporis fabrica

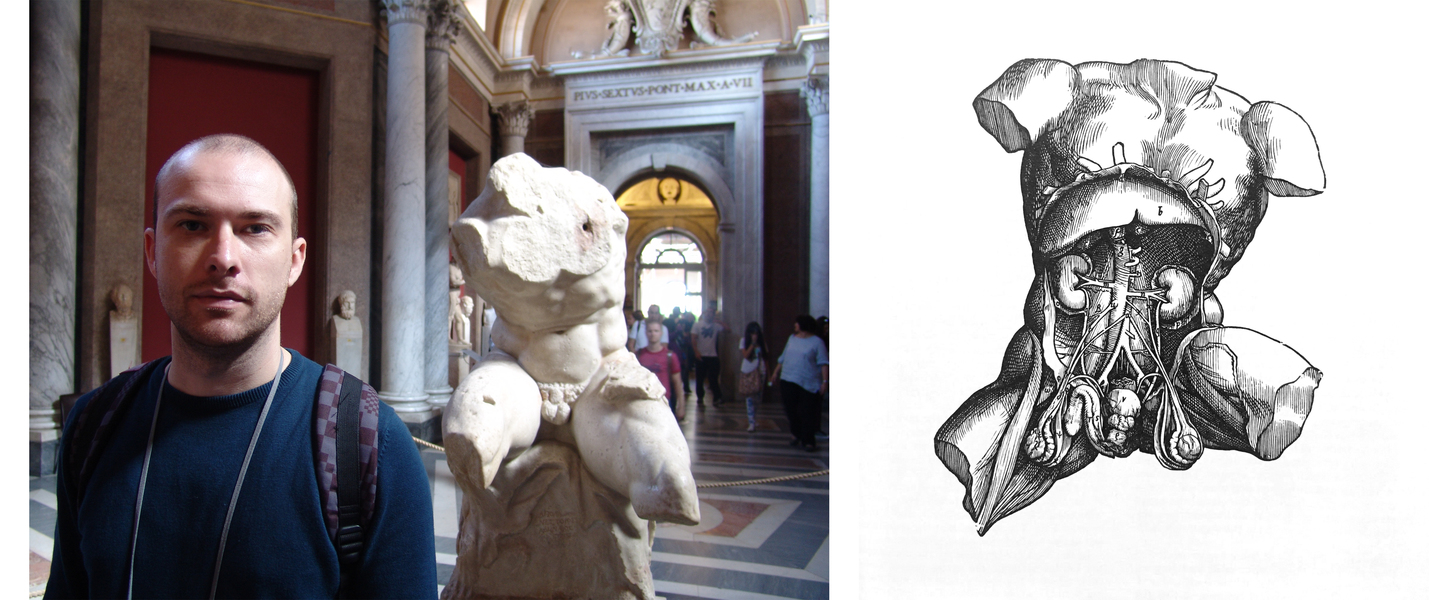

With the illustrations in De humani corporis fabrica, for the first time in medical illustration, the rules of perspective, light and shadow and spatial plans were applied in order to capture the realism of the objects. Through illustrations, Renaissance aesthetics was used as a frame in which human anatomy, based on the new knowledge of Vesalius, was displayed. The illustrations follow the Renaissance concept of body shape, imprecisely and robustly, reflecting the passion of Renaissance humanists towards antiquity, especially for ancient sculpture. Illustrative solutions include illustrations of fragments of ancient sculptures that were used as models for anatomical displays of the insides, such as the example with the Roman marble sculpture Torso Belvedere, which the illustrator used to portray the urogenital tract. The bodies are set in Italian landscape panoramas, where hills, valleys, rivers, Roman baths, churches, and even cities can be seen in the distance. At that time doctors shared the same desire with artists to study the human body. Artists, above all, strove for a plausible display of nature and were obsessed with the idea of individual beauty and optical accuracy of vision. It is not erroneous to say that they contributed to the creation of medical illustration as a special scientific and artistic discipline. In this sense, in the letter to Oporinus, Vesalius stated that it is extremely important for him to pay attention to the artistic aspect of the print. He insisted that the print contains all the details and information the artist etched on the printing plates, emphasizing the thickness of the lines that create a shadow gradation.

The illustrator, who has a special place on the title page and is represented as a young man standing in the second row of the theater as holding an open book, was undoubtedly part of Vesalius' lectures and was his frequent companion, who painted all the details he observed. The artist officially headed as the creator of the illustrations for De humani corporis fabrica is Titian's pupil, Renaissance artist Jan Stephan van Kalkar (1500-1546), although it is assumed that Titian, Domenico Campagnola and Vesalius himself also took part in the whole illustrative project.

left: The author in front of Torso Belvedere, Musei Vaticani, right: Illustration from De humani corporis fabrica

What Vesalius did through these collaborations speaks not only of his openness to knowledge, but also of his exceptional sense of the nature of knowledge. Oporinus and Kalkar are part of the creation of a total design in an organizational sense, by including various professional or creative aspects in the process of creation. This process resulted in the publication of one of the most beautiful and most important books of the modern world. De humani corporis fabrica, inspired generations of doctors, scientists and artists, and still inspires and attracts our attention, leading us to look through the wooden benches of the theater and see the work of Vesalius. In the upcoming centuries medical illustration experienced immense growth, and today we can find many medical books that possess not only scientific but also high artistic value. With De humani corporis fabrica Vesalius laid the foundations of modern medicine, but also posited curiosity, experiment and personal experience as key elements of scientific thought. Today, medicine is taught on these postulates. To a larger or lesser extent, anatomical atlases follow that organizational logic. In spite of the mistakes of Vesalius’ anatomical methods, De humani corporis fabrica is a synonym for the transfer of knowledge as an artistic skill.

\\\

Ilija Prokopiev (1985) is an interdisciplinary artist and researcher, co-founder of PrivatePrint.

Bibliography:

Saunders,J.B. de C.M. and O'Malley, Charles D.. (1973) The Illustrations from the Works of Andreas Vesalius of Brussels, New York: Dover Publications

Rafkin, Benjamin A., Acerman, Michael J., Folkenberg, Judith (2006). Human Anatomy - A Visual History from the Renaissance to the Digital Age. New York: Abrams

Станојевић, Др Владимир (1953). Историја медицине. Београд: Медицинска књига